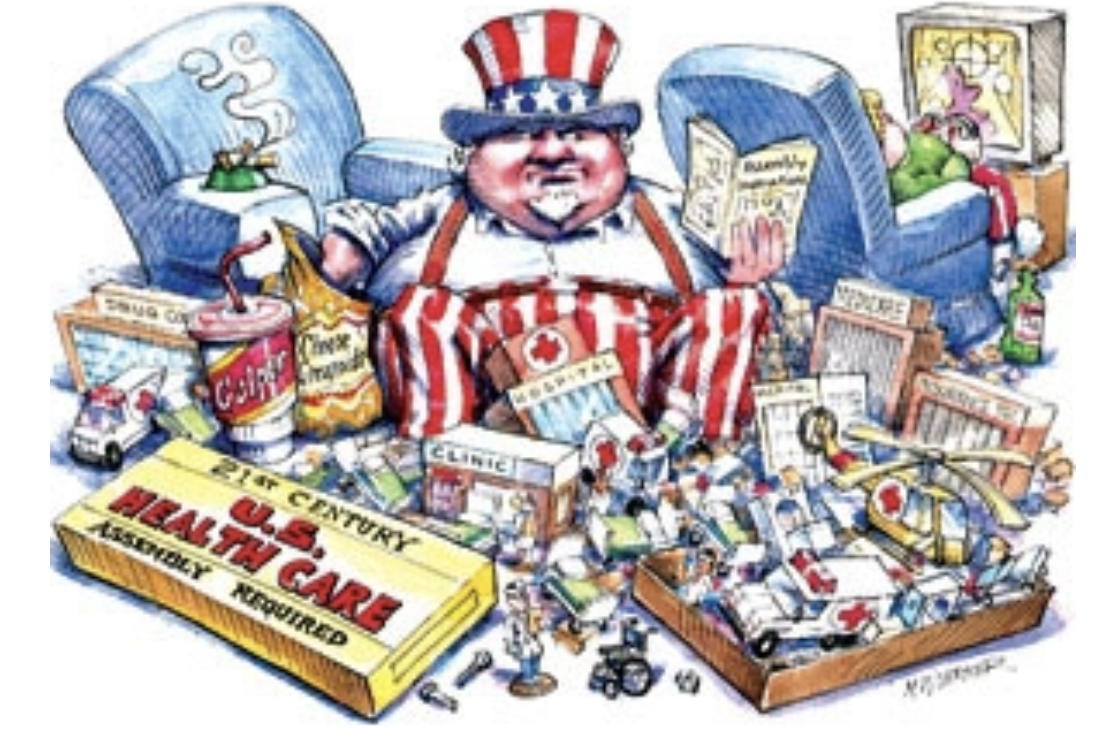

Image via Politico

***

So much of American culture is centered around presumption. This is most uncontestable illustrated by our national obesity rate. The UNHCR recently found that the global rate of child obesity is surpassing the global rate of child malnutrition. Obesity rates in wealthy countries such as America have been consistently high due to our accessibility and manufacturing of hyper processed food. This is no longer just a domestic dilemma, but an international demonstration of how globalization, trade policy, and corporate influence shape human health.

The worldwide expansion of Western food industries, combined with aggressive marketing and unequal access to nutritious alternatives, has created a new kind of global health crisis. Obesity now represents both a humanitarian and political challenge: it strains public health systems, exacerbates inequality, and exposes the ethical failures of international trade and aid structures. Addressing obesity, therefore, requires not just medical interventions, but a reexamination of how international politics and humanitarian frameworks perpetuate or can help mitigate this expanding global burden.

Worldwide adult obesity has more than doubled since 1990, and adolescent obesity has quadrupled. The economic toll of obesity extends far beyond healthcare costs, affecting workforce productivity, trade relations, and development priorities. Politically, it exposes global inequities—where multinational food corporations profit from unhealthy consumption patterns in vulnerable regions. As obesity becomes a transnational crisis, it demands coordinated policy reform and humanitarian accountability across international systems.

Within the US, agricultural subsidies play a major role in domestic consumption of ultra-processed foods. The most highly subsidized crops,corn, soy, wheat, and rice,are the most abundantly produced and most consumed, often in the form of ultra-processed foods. This has caused up to 70% of the American food supply to be composed of ulta-processed food. Our domestic obesity rate is 40.3%, while the global obesity rate is estimated at 16%. While this variance can partially be explained by our manufacturing abilities as a wealthy industrialized country, this is partially due to American overconsumption culture.

The international obesity rate has more than doubled between 1990 and 2022. This swell is largely caused by trade agreements that increase access to cheap, processed food globally. Trade policies regarding liberalisation, export promotion, import substitute measures, protection of domestic industries and support for foreign direct investment have also contributed to the increased availability of foods associated with the nutrition transition. For example, after countries join a US Federal Trade Agreement, sales are estimated to increase by 95% per capita per annum for ultra-processed products. As a global leader our promotion of malnutrition on a global scale is terrifying.

Diets in developing countries are primarily shaped by multinational food corporations. Obesity has been increasing exponentially in several regions of the developing world, particularly Latin America and the Caribbean and North Africa. Multinational corporations such as McDonald’s and Coca-Cola are largely responsible for the double burden of obesity and disease prevalence in developing countries especially because these countries lack nutrition education. In Latin America 15 years ago there were 100 McDonald’s outlets, whereas today there are 1l,581, with one-third located in the urban areas of Brazil. Similarly, India and Nigeria are listed among the top emerging markets in the CocaCola Company’s Annual Report. This global corporate expansion reinforces my central claim that obesity is not merely a matter of personal choice or public health, but a politically engineered humanitarian crisis driven by the unequal power dynamics of globalization and international trade.

If current trends continue, by 2060, the economic impacts of obesity and associated overweight (OAO) are projected to rise to 3.29% of global GDP. The greatest increases will occur in lower-resource nations, where total economic costs are expected to rise twelve to twenty-five times higher than in 2019. In contrast, high-income countries will see roughly a fourfold increase over the same period. These figures reveal a grim paradox: while wealthy nations are the primary exporters of ultra-processed food and the policies that sustain them, the heaviest economic and social burdens fall on the developing world. Obesity costs the US healthcare system almost $173 billion a year. Developing countries that are the victims of America-based multinational corporations do not have the wealth nor infrastructure to support the health issues that will arise from projected increases in obesity.

Many low- and middle- income countries face a double burden: a high prevalence of both undernutrition and obesity. As per capita income increases, the burden of obesity shifts to the poor and to rural areas.The highest rates of the ‘double burden’ fall in the Caribbean and Latin America. The double burden stunts a country’s development goals by impacting economic productivity. Countries facing both undernutrition and rising obesity are often those most vulnerable to external economic pressures, foreign direct investment by multinational food companies, and the importation of cheap, ultra-processed products that displace local food economies. As a result, their public health systems become strained on two fronts: they must treat nutrient deficiencies rooted in poverty while also absorbing the long-term costs of obesity-related diseases. This tension reveals the humanitarian dimension of global obesity policy. The same global economic forces that undermine nutritional security also inhibit a country’s ability to meet development goals, making obesity an unmistakable symptom of deeper geopolitical imbalances.

While stunting sustainable development goals in low income countries, obesity rates can also have geopolitical implications. Obesity has a major impact on national economies by reducing productivity and life expectancy and increasing disability and health care costs. In 2015 the UN developed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to achieve a more sustainable future. The second of these goals is zero hunger. While addressing this Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) often supply food aid to countries in crisis which rely on American surplus crops such as corn,soy, and wheat. While this food aid assists the population struggling with hunger; it is not nutritious and can contribute to malnutrition because of how carb-dense they are.

Several countries have demonstrated that structural policy interventions can counteract the harmful effects of corporate-driven unhealthy eating. For example, Mexico’s soda tax, introduced in 2014, led to a 6–10% drop in purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages in its first two years, with the biggest reductions among lower-income households. A modeling study estimated that this tax, when combined with warning labels, could prevent over a million future obesity cases and save the government roughly $1.8 billion in obesity-related costs over five years.

In Chile, the 2016 Law on Food Labeling and Advertising introduced black “stop-sign” warning labels on foods and drinks high in sugar, sodium, saturated fat, or calories, while also restricting marketing to children and banning sales of such products in schools. Within 18 months, sugary-beverage consumption in representative Chilean households dropped by nearly 24%. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has moved to limit children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing: starting in October 2025, adverts for high-fat, salt (HFSS) or sugar products on television will be banned before 9 pm. Early evidence suggests such marketing restrictions can significantly reduce household purchase of HFSS products.

This evidence underscores a core point of my argument: obesity is not solely a matter of personal responsibility but is deeply rooted in political and economic structures. Recognizing the outsized influence of multinational food corporations, many global health advocates and international bodies are now pushing for policies that limit corporate marketing power in developing countries. The World Health Organization has urged nations to adopt comprehensive restrictions on marketing unhealthy foods to children, and several countries—particularly in Latin America—have begun to act. Brazil’s Consumer Defense Code classifies advertising to children as abusive, and Peru has introduced mandatory front-of-package warning labels similar to Chile’s model. In addition, some African nations are experimenting with tariffs on sugary beverages and highly processed imports as a way to protect local food systems and curb rising obesity rates. Internationally, frameworks such as the UN’s Political Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases encourage member states to regulate supply chains and restrict corporate interference in public health policymaking. These measures, although unevenly implemented, demonstrate a growing recognition that meaningful progress requires reclaiming political authority from multinational corporations and shielding vulnerable populations from predatory marketing. They represent an emerging shift toward global accountability—one that begins to challenge the very structures that fuel the humanitarian dimensions of the obesity crisis.

Though there is a lot of beauty to American culture, our projection of overconsumption of ulta-processed foods negatively impacts developing countries. The global spread of American eating patterns—driven by trade liberalization, relentless corporate marketing, and the growing dominance of Western fast-food chains—has reshaped diets in places that were once protected by strong local food traditions. As a result, communities with limited healthcare infrastructure now bear the medical and economic fallout of a crisis they did not create. This dynamic reinforces the central theme of my argument: U.S. economic influence, when left unchecked, can unintentionally destabilize global health and deepen humanitarian inequities.

***

This article was edited by Ayden Suber and Ella Keddy.