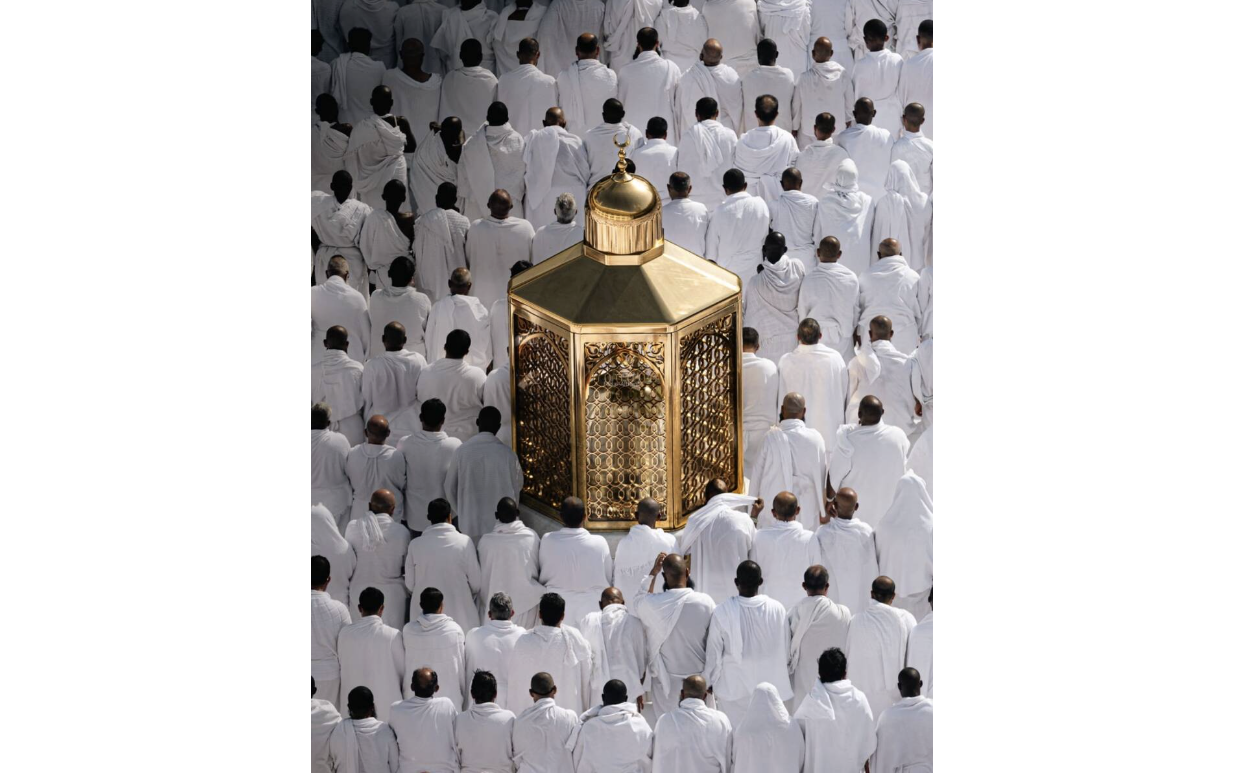

Photo via Faisal Al-Thaqafi (Arab News)

***

Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Hajj and Umrah Tawfig F. Al-Rabiah stated that the Kingdom achieved ‘unprecedented’ efficiency during this year’s Hajj pilgrimage to Islam’s two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, which Muslims from all over the world travel to complete. Reports have indicated a sharp decline in fatalities compared to last year’s Hajj, with a record number of 1,300 people dying after temperatures exceeded 125 degrees Fahrenheit. However, the Hajj, which operates in accordance with the lunar calendar, has taken place within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) hottest months since 2015. The drastic drop in deaths this year may be due to new policies implemented to restrict government-approved attendance to Mecca and Medina. Despite significant financial investment in crowd control measures and heat-resilient infrastructure, approximately 83% of all Hajj pilgrims in 2024 lacked official permits, thereby restricting access to potentially life-saving services. To seek out unregistered pilgrims, Saudi authorities have rolled out a new fleet of drones to monitor entrances into Mecca, and security forces have also raided hundreds of apartments in search of people hiding out in the area. Through these efforts, Saudi police forces have claimed to stop 269,678 permit-less pilgrims from entering. The Saudi government typically issues fines of up to $5,000 (€4,400) or even decade-long bans from the country to pilgrims lacking sufficient permits. But what is the larger scale social infrastructure which allows for the continuation of this phenomenon?

A major issue with the Hajj evaluation process concerns the financial constraints applied to worshippers. For many Muslims in the Global South, Hajj is a duty one can only undertake after working for decades to accumulate the funds necessary. Many Muslims work in countries highly susceptible to weak economies and structural instability, resulting in a large number of unregistered pilgrims being elderly. Indonesia, a country with over 200 million Muslims, automatically receives the largest annual Hajj quota from KSA out of all other nations, around 229,000 in total in 2023. However, in 2015, 3,500 permit reservations were relinquished due to the financial constraints imposed on Indonesians in the wake of a domestic financial crisis, making the rupiah Asia’s second worst-performing currency. This is not an uncommon phenomenon by any means; in Egypt, the most populous Arab country, the cheapest government-sponsored pilgrimage currently costs around $6,000. This is fuelled by the sharp devaluation of the Egyptian pound, which has lost more than 50% of its value against the US dollar from March 2022 to June 2023. Because the overall cost of living continues to rise, many families who have been saving for the Hajj for years are forced to use that money in the wake of financial or political disarray. By contrast, the only four nations that are allowed to go on Hajj without a visa are not the most populated, but the wealthiest: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates.

That being said, Saudi Arabia generates substantial profits from the Hajj and is often reliant on poorer nations for the bulk of its annual revenue. A comparative pricing analysis of Mecca’s religious tourism revealed that countries with wealthy economies charge much higher prices for Hajj packages than those with moderate economies. However, the overall Hajj revenue is the highest (up to 940 million dollars) in the most populated Islamic countries, like Indonesia. The money generated by the permitting system is a significant factor that makes financing continued pilgrimage improvements possible. In recent years, Saudi Arabia has implemented a series of civic engineering projects to facilitate travel for registered pilgrims, including the installation of a new online database for travelers and the creation of high-speed railways from Jeddah to Mecca. Some argue that this is the KSA controlling both the means of acquiring profit, in addition to the money itself. Through the business of creating high-end infrastructure, Saudi Arabia can diversify its economic landscape in the wake of clean energy emerging as a competitor to oil revenue worldwide.

The Hajj today bears little resemblance to the journeys of the pre-industrial age. The application of modern technology to the Hajj has helped make it safer, easier, and more accessible for those who can afford it. KSA generates over $600 million annually from the Hajj alone and has invested billions of dollars in expanding infrastructure in Mecca and Medina, including multilevel pathways, high-speed trains, and sophisticated crowd-control systems. The Hajj has always attracted business investments throughout Islamic history. For centuries, major overland caravan routes traversed Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad, with merchants from around the world taking advantage of Mecca’s pilgrim population to sell their goods. Early Quranic commentaries explain the utility in conducting business on pilgrimage through verse 2:198, which states, “there is no blame on you for seeking the bounty of your Lord during this journey…” There is a pre-existing religiously sanctioned security in using Mecca as a strategic location for business. The true challenge that business poses to the Hajj is not in the means through which it is implemented, but in its effect on the overall spiritual experience in the name of religious duty. There are legitimate concerns over the necessity of mass commercialization in the Holy City. What is typically a journey of faith and asceticism is being transformed into a materialistic ritual for the pilgrims fortunate enough to be able to enter Mecca. The logistics of Hajj, as a yearly event, cannot keep pace with the breakneck speed at which modern society operates. The primary way for Saudi Arabia to manage that flow is by directing it towards activities that support the domestic economy. Through a combination of consumerism and religious tourism, the development of luxury hotels and restaurants near God’s house has been permitted for over 2 billion pilgrims. Simultaneously, individuals who have sacrificed their livelihoods and even their lives to get to Mecca remain without a fraction of the same accommodation. The use of religious tourism for wealthy pilgrims stands in contrast to the countless individuals who have waited for years for a spot in the quota.

Ultimately, the matter of how many people are allowed to enter the country each year, and on what terms, is an issue that has increasingly become a matter of concern for modern nation-states struggling to accommodate their 2 billion adherents. It is not the responsibility of a single government to finance the pilgrimage of a citizen, but the current system remains corrupt and inequitable. Infrastructure in KSA should prevent illegal entry into their holiest cities, but that shouldn’t have to mean turning towards profit garnered from collaboration with business conglomerates in order to do so.

***

This article was edited by Nicholas Meetze.