Photo via X

***

Picture sitting in class as your teacher suddenly takes scissors to your hair—not out of anger, but because it breaks the rules. This is everyday life for some Thai students, where strict grooming regulations dictate that boys must have crew cuts, and girls’ hair cannot extend past their ears. What is seen in schools is a reflection of how authoritarian values are taught, normalized, and internalized from school to society. Could these grooming regulations act as a metaphor for Thailand’s larger struggle between obedience and individuality?

These strict regulations date back to 1972, when they were imposed by a military government to enforce discipline and conformity in schools. The order came from a ruling junta that had seized power in a coup, reflecting the broader pattern of unelected military leaders dominating Thai politics. Over the following decades, the alliance between the military and monarchy instilled a culture of loyalty, hierarchy, and obedience across society. Schools became a microcosm of this authoritarian order, where students learned to submit to authority and internalize discipline.

In this context, strict grooming rules were less about hair and more about teaching conformity from a young age. This pattern of control extends beyond schools. According to Human Rights Watch, Thai authorities have charged more than 80 people—including at least six minors—under lese majeste laws for peacefully expressing pro-democracy views. These laws prohibit defaming, insulting, or threatening the monarchy; breaking them can result in penalties of three to fifteen years in prison per offense. “By punishing outspoken children with lese majeste charges, the Thai authorities are seeking to intimidate peaceful critics… regardless of their age,” said Brad Adams, Asia Director at Human Rights Watch. This shows how the state’s push for obedience in classrooms reflects a larger effort to silence youth voices and discourage dissent. While others frame it as preserving Thai values of neatness, modesty, and respect for authority, these rules also reveal how deeply political control can reach into everyday student life.

What started as a government mandate manifests today in the seemingly small—but deeply controlling—ritual of cutting students’ hair. In July 2025, 50 girls at a Ratchaburi school had their hair cut simply for extending past their uniform name tags. These trims were not ordinary; they were botched, uneven, impossible to ignore. Another student, a 15-year-old from Southern Thailand, was forced to have his hair cut publicly by a teacher and described the experience as deeply embarrassing and scarring. Watcharin Keawtankham, a barber in Mae Sot, frequently fixes these botched school haircuts, saying they are meant to humiliate children. He once posted a photo of a student’s head with a disturbing bald spot, demonstrating how each of these moments turn humiliation into a ritual of control.

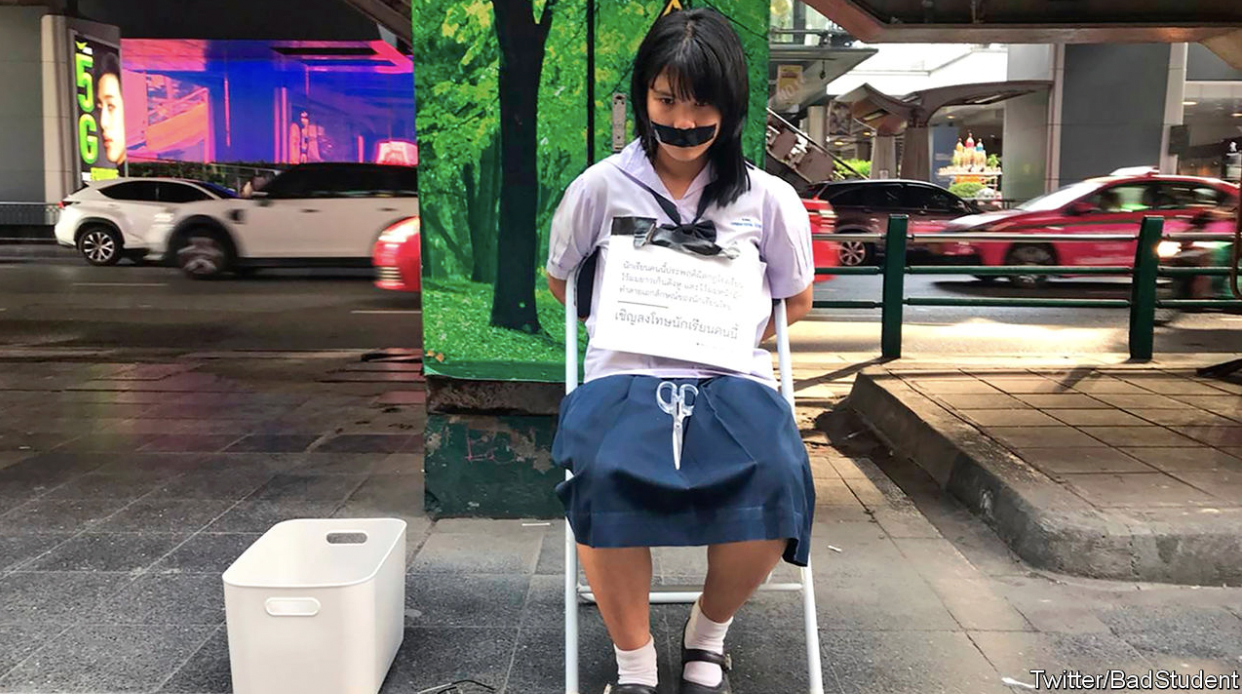

But not all students remain silent. Laponpat Wangpaisit, 22, founder of the student rights group Bad Student, explains that these regulations are designed to make citizens “easy to rule.” Members of Bad Student protest outside the Education Ministry in Bangkok in their school uniforms. They tie white ribbons, symbols of protest and purity, and cover their names with duct tape—showing both unity and fear of punishment. Students raise the three-finger salute, borrowed from The Hunger Games, signaling resistance to oppression and solidarity with one another. These acts of protest transform the classroom from a space of control into a subtle stage of rebellion. Public humiliation through haircuts reflects a deeper system of authoritarianism, where obedience is demanded and individuality suppressed. Even in small gestures, students assert their own freedom, showing that personal choice can push back against a culture of conformity that extends far beyond the school walls.

Activists and students argue that this issue reflects a much broader struggle over democracy and freedom in Thailand, where authorities prioritize servility over individual liberty. While Thailand is a constitutional monarchy, real power often rests with the military rather than elected officials, reinforcing a culture where hierarchy trumps democracy. What began as a dispute over grooming has evolved into a national symbol of this larger struggle, showing how authoritarian tradition collides with youth-led calls for personal freedom. Students describe school as “the first dictatorship in their lives,” and the Bad Students view their campaign for school reform as part of a wider effort to challenge authoritarian rule in the country. They have attended national rallies, demanding the dissolution of Parliament, a new constitution, freedom of expression, and reform of the monarchy.

Although the government claims to allow student expression, in practice, police and local officials harass and intimidate student activists. Hundreds of students report threats, questioning, and punishment for small acts of dissent, like wearing white ribbons or giving the three-finger salute. These incidents show how even minor gestures of resistance are treated as challenges to authority, reinforcing the lesson students learn in school: questioning power comes with real consequences.

The hierarchy in Thai schools extends well beyond students. On March 16, Wanida Rangsrisak, a teacher at Baan Batchathani School in Roi Et, shared a screenshot of a message from her principal on Facebook. The principal wrote: “I feel something inappropriate happened today—a teacher sat on my chair. Though I did not see it, while I was a teacher, I never once sat in an executive’s chair and never dared put myself at the commander’s level.” Though harmless, the principal treated it as a violation of hierarchy and respect. After public backlash, the Office of the Basic Education Commission removed the principal and launched an investigation. This incident exposes how deeply authoritarian thinking is embedded in Thai educational culture. As Tanawat Suwannapan, a Bangkok teacher, described it, the event was “only the tip of the iceberg.” Some principals reportedly make teachers serve them food, run personal errands, or even have female teachers act as waitresses at school events. These examples reveal institutionalized servitude and passivity, showing that the same lessons of hierarchy and submission taught to students are also enforced among teachers.

Although a top Thai court overturned the national hairstyle directive in March 2025, many schools, especially in rural areas, continue to enforce the old, strict standards. This cascading hierarchy, from State bureaucracy down to principals, teachers and finally, students, reveals how deeply authoritarian values are embedded in both education and society. Something as seemingly small as a haircut becomes a microcosm of control, a lesson in submission, and a reflection of Thailand’s broader struggle between authority and individuality. As Phatit Kalaphakdee, 16, who goes by Rin, reflects, “Hair can give you confidence, or it can ruin your day.” The debate over haircuts is ultimately a debate over freedom, how much control a state should have over its citizens’ bodies, and how far conformity should reach. For Thailand’s youth, the fight over hair is a fight for dignity, democracy, and the right to define themselves.

***

This article was edited by Fatimah Waqas.