Introduction

Most Americans, especially those unfamiliar agriculture, might associate the term “green gold” with a naturally occurring gold-silver alloy, or perhaps the paint color of a particularly artistic teen’s bedroom, rather than the product of a multibillion-dollar agricultural trade network that they themselves help sustain—often at the expense of Mexican lives, land, and liberties. The avocado, known as green gold by farmers, has become a crucial Mexican export in recent years. In response to soaring international demand, global avocado production rose more than 50% from 2018 to 2023, with over a quarter of that output coming from Mexico alone. In 2024, Mexico produced 2.77 million metric tons of avocados, exporting over 80% of them to the United States: the largest consumer of avocados worldwide.

The growth of this trade network has had numerous consequences on Mexican communities, especially in the state Michoacán where ¾ of avocados are grown. Some effects are positive, such as nation-wide economic growth and increased opportunities for low-skill workers. Many, however, are incredibly harmful. The avocado trade has been correlated with a rise in cartel violence, ecological damage, water scarcity, farm labor exploitation, and the erosion of the avocado’s historic significance in Indigenous communities.

As the primary sponsor of avocado production in Mexico, the United States bears responsibility for its impacts on the nation’s citizens. It is impossible to examine the present-day trade relationship between the two countries without acknowledging the history of the U.S. as a settler-colonial nation. Indigenous populations in the Americas—many of whom still live in Mexico—have historically been oppressed and exploited for the benefit of Europeans and their immigrant ancestors—many of whom still live in the United States.

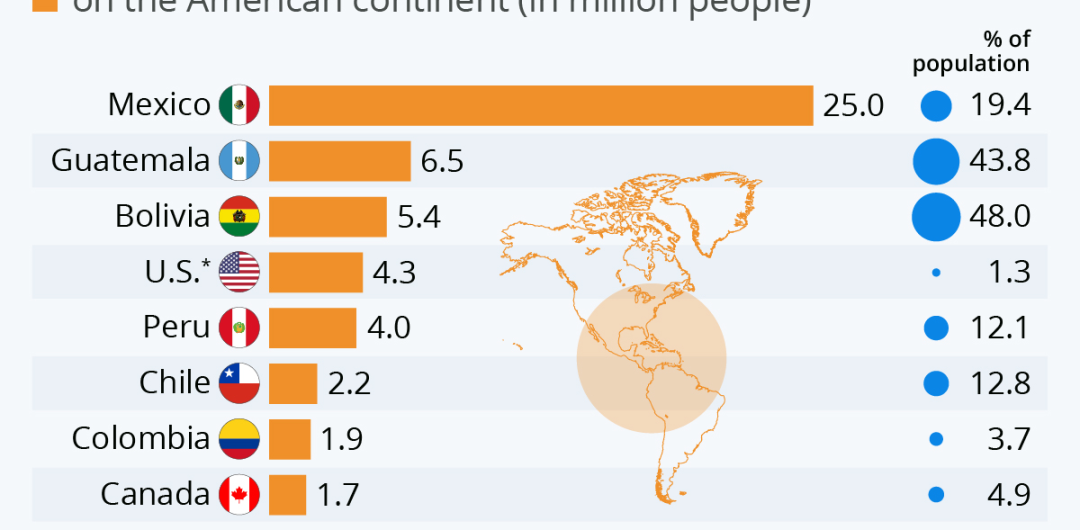

Figure 1

Graphical representation of Indigenous populations in North American countries. Source: Indigenous World 2021

***

To analyze what exactly this oppression is and what it means for Mexican communities, I will utilize Iris Marion Young’s five faces of oppression: exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence.

Youngian Framework

Dr. Iris Marion Young, one of the most important feminist philosophers of the 20th century, outlined five faces of oppression—exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence—applicable to many social contexts. Each can impact a social group independently or in conjunction with one another, and all of them are present in the oppression Mexican communities experience at the hands of American consumers.

Key here is the note that “oppression designates the disadvantage and injustice some people suffer not because a tyrannical power coerces them, but because of the everyday practices of a well-intentioned liberal society” (p. 41). While there are certainly some individuals in unique positions of power who directly oppress Mexican communities through the avocado trade, most Americans are not in that position. Most Americans will never even meet the people who grow their avocados. Young’s framework deconstructs the complex trade relationship in order to identify the ultimate impact that American demand has had on the people of Mexico: oppression.

Exploitation

Young begins her outline by identifying exploitation, which she calls the “transfer of the results of the labor of one social group to benefit another” (p. 49). Exploitation is about relational power imbalances that result in one group harvesting the fruits of another’s labor (literally—avocados). American consumers benefit from an overabundance of cheap avocados throughout the entire year while some in Mexico can no longer afford the fruit because of its rapidly inflated price.

Exploitation is also evidenced by the poor labor conditions for Mexicans farm workers. Packing house employees in the heart of Michoacán work 12-hour days for $130 a week, and harvesters work for around $6/hour without benefits. Much of the Mexican avocado labor market is controlled by large export companies subject to the labor provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Formally, Mexican workers in the avocado industry have the right to collective bargaining, social security, and freedom of association. In January of 2024, employees of RV Fresh Foods—an avocado distribution company within the Association of Avocado Exporting Producers and Packers of Mexico (APEAM)—filed a petition under the USMCA claiming that those rights were violated. They described “resistance from APEAM to unionize…they do not want to provide social security to 63,000 workers.” Workers also extended accusations of bad practices to other avocado companies, including WestPak, Del Monte, and Global Frut. The workers’ claims were validated, and in the spring of 2024 APEAM was ordered to pay reparations and amend their practices. It is unclear whether the remediation has been successful, and what other kinds of labor rights violations Mexican workers are currently facing.

Largely, Mexican workers have not seen the gains of the increased avocado trade catering to U.S. demand. Of the ten largest global avocado producers, controlling a market collectively worth over $2.4 billion, six of them are headquartered in the United States, and only one in Mexico. The ignorant American that benefits from cheap avocados in January is undoubtedly participating in a relational form of oppression that, amongst others, can be considered exploitation.

Marginalization

After exploitation, the second face of oppression is known as marginalization, referring to “people the system of labor cannot or will not use…thus potentially subjected to severe material deprivation” (p. 53). Marginalization can be seen in the avocado trade with regard to the trade barriers that reduce Mexican workers’ freedom and the associated costs of pursuing avocado agriculture.

Historically, avocado imports to the U.S. were heavily restricted by phytosanitary restrictions out of fear for invasive species and pests. In 1997, restrictions were lifted, but only for the state Michoacan, and in 2022 restrictions were lifted for the additional state of Jalisco, Michoacan’s bordering neighbor. Avocado imports have also faced barriers over the years relating to security measures, incidental suspensions, and most recently, threats of tariffs. Security measures and incidental suspensions can largely be traced back to the presence of cartels in avocado exporters and other security threats at the southern U.S. border. As of now, there are no tariffs on avocados from Mexico, but U.S. President Donald Trump was notorious in his campaign for promises of high tariffs on Mexican goods, and his first year in office has not looked promising for Mexican communities and products.

Increased trade barriers with Mexico directly reduce the freedom that Mexican workers have to pursue avocado production. Avocado being the cash crop that it is, many workers in Mexico are faced with the trade-off between the high labor productivity and profitability of avocado farming, and the community food needs and high costs of interregional trade that discourage new entrants to the market. As found by Alberto Rivera-Padilla, economist at Tulane University, “reducing trade costs in Mexico to the U.S. level would raise the ratio of employment in cash crops to staples by 15 percent and generate a 13 percent increase in agricultural labor productivity.” This increase could be incredibly meaningful for the lowskill agricultural workers who seek to gain from working in the avocado industry. Many of these potential avocado farmers are being sidelined by the high costs of trade and the threats of increased tariffs, constituting marginalization.

Powerlessness

Powerlessness—the third face of Youngian oppression—describes groups of people who have no authority over others and lack power over their governments, economic conditions, and employment prospects. Mexican workers are often treated as pawns in an increasingly interconnected Mexican-American avocado industry of conglomerates. Internal migration pressures and changing politics (domestic and international) create instability in the lives of agricultural workers.

Nearly half of Mexican farm workers are internal migrants, drawn to move either permanently or seasonally away from their home state to seek the economic opportunities of agriculture. While these opportunities can be significant—peak harvesting wages can reach $473/month, which the largely uneducated agricultural workforce would be unable to make in any other industry—they also demonstrate how vulnerable Mexican farm workers are to the transient demands of Americans. Most of these agricultural jobs did not exist before the explosion in U.S. demand for avocados, meaning that they could disappear just as quickly.

Furthermore, the economic advantages found in the avocado industry can come at the expense of instability and deprivation in other areas of life. For instance, 20% more Mexican farm laborers who work locally live under the poverty line compared to temporary internal migrants. Escobar et al. attributes that difference to the tendency of internal migrants to “leave their children in the care of relatives in their hometowns.” If these workers had the opportunity to live above the poverty line while staying in their home state with their children, they quite possibly would. However, that power has been stripped from them by the mass demand of U.S. consumers and the policies of U.S. imports that command avocados only be produced in Michoacán and Jalisco.

Cultural Imperialism

After powerlessness, Young turns to cultural imperialism, which is perhaps the most nebulous face of oppression. Cultural imperialism when a society’s most prolific and socially acceptable cultural products are a reflection of one social group’s perspective projected onto oppressed groups. This form of oppression alienates groups from their own history and identity.

When the avocado became commoditized as a high-value staple of the modern American diet, its cultural heritage and Indigenous roots were overwritten by export demand. The avocado ceased to be a spiritual fruit consumed by Aztec peoples to enhance fertility, and turned into a breakfast ingredient associated with holistic health, chip dips, and Super Bowl commercials.

In Puebla, Mexico, the home of the avocado, Indigenous peoples have been consuming the fruit since roughly 8,000 BCE, nearly 5,000 years before its domestication. The first breeders of the fruit in the U.S. were in California in the early 20th century. Around the same time, imports of avocados from Mexico were banned. Within a span of 20 years, avocados shifted in the minds of Europeans and their American descendants from an exotic, culturally Mexican fruit, to a Californian fruit masquerading playfully as Mexican. Viridiana Hernández Fernández defines U.S. agricultural imperialism as the process of Americans “extracting plant diversity from the Global South and protecting the nascent agricultural industry from outside competition” (2024). Farmers and agricultural scientists in southern California created a domestic competitor to the Mexican avocado colonizing it both biologically and culturally.

Food and eating are key anthropological tools to identity creation and cultural differentiation. Eating is also biologically necessary, so taking control of the avocado and its cultural narrative passes power to the imperial state over both material and conceptual autonomy of Mexican peoples. American cultural imperialism via the avocado is further emphasized by the massive ecological footprint Americans are leaving on Mexican land. Since 2014, an estimated 70,000 acres of land in Michoacán were cleared to create avocado farms. The land itself is being terraformed to serve American needs, physically demonstrating the phenomenon of Mexican culture being warped to fit an American narrative.

Violence

The fifth and final face of oppression described by Iris Marion Young is violence, specifically random and sporadic acts of violence perpetrated against a social group because of their unique identity. Mexican avocado workers are subject to a host of dangerous conditions throughout the production process of a fruit that, ultimately, will go into an American stomach.

First, there is the danger associated with organized crime in the avocado industry. While crime syndicates usually proliferate illicit products, any newly lucrative market can attract such groups and prompt violence against rivals to maximize profits. In the past decade, Mexican cartels have attained an enormous share in the avocado market, leading to the deaths of farmers, farm laborers, and others employed in the industrial avocado food chain. Since 2005, the homicide rate in Mexico has more than doubled (reaching 54 homicides/100,000), which has been explicitly associated with the rise in production and value of the avocado.

Violence is also evident in the damage taken by Mexican land and the consequential suffering of local Mexican communities. Avocado farming often entails deforestation, as land is cleared to plant avocado trees and provide them uninterrupted access to sunlight. Deforestation has many downstream effects, including worsening impacts of climate change. In the avocado-producing regions of Michoacán, temperatures and frequency of severe weather events have both increased in the 21st century.

The avocado is an incredibly water-intensive fruit, and so, predictably, water scarcity has become a major concern as production has increased. 9.5 billion liters of water are used each day in the production of Michoacán avocados. This strains local aquifers, leading to water shortages for local communities and ecosystems, and even has unexpected negative consequences, such as causing small earthquakes.

To all of this, international companies, American buyers, and the U.S. government itself has turned a blind eye. The primary group who suffers the consequences of illegal and ecologically exhaustive avocado farming in Mexico are Indigenous communities; this is also the group most frequently threatened with violence and made to stay silent. In an interview with Climate Rights International, an enviro-humanist non-profit, an Indigenous community leader in Michoacán spoke for the entire avocado region when he claimed “if you point the finger or talk, they’ll kill you…There is no freedom to act due to fear of reprisals.” Environmental officials in Mexico fail to enforce the laws prohibiting deforestation, water overuse, and other agricultural practices that degrade the environment either out of fear or corruption.

Despite these obstacles, there have been leaders throughout the years seeking to contain the environmental and humanist problem. Primarily, officials have sought to keep avocados grown on illegally deforested land away from the immense profits of the U.S. avocado trade. In 2021, Mexican officials proposed adding a “no illegal deforestation” requirement to USDA inspections of avocados for American import. The U.S. officials refused this policy, and today “virtually all” new avocado farms (upwards of 70,000 acres) in Mexico come from illegally deforested land.

Avocados from illegally deforested lands are purchased by U.S. distributors and sent to supermarket chains including Walmart, Whole Foods, Kroger, Albertson’s, Costco, Target, and Trader Joe’s. These stores thereby implicate their consumers in the chain of violence tracing back to Mexican communities. One avocado farmer in Madero, Michoacán, who was himself kidnapped for protesting deforestation, expressed his wish that American consumers knew what was really going on: “behind every avocado that people in the United States eat, there is a bloodstain, a dead person, a missing person.”

Conclusion

The global avocado trade—celebrated in American kitchens as a symbol of health, modernity, and prosperity—is, for many Mexicans, a mechanism of ongoing oppression. Iris Marion Young’s five faces of oppression demonstrate that this system is not an unfortunate byproduct of globalization, but rather a structural continuation of settler-colonial power. Exploitation manifests in the transfer of labor’s value from Mexican workers to American consumers; marginalization in the exclusion of small farmers and Indigenous communities from fair participation; powerlessness in their inability to influence trade policies or corporate practices; cultural imperialism in the erasure and commodification of the avocado’s Indigenous meaning; and violence in the physical and ecological harm perpetuated by cartel control and environmental devastation.

Mexican oppression relative to America does not implicate all Americans as oppressors. Instead, most Americans (including myself) are unconscious participants in a global structure of colonial continuity. Recognizing the “blood fruits” of the U.S.–Mexico avocado trade compels us to question our own participation in systems of inequity. As consumers, we can demand rigorous certification standards for sustainable farming, fair trade, and environmental impact on avocado imports. There is also a need to make corporations accountable, especially in instances where corruption and violence prevent government systems from functionally enforcing the law. Finally, consumers can themselves reduce their avocado consumption. There is an immense value in understanding the price of objects that have become part of Americans’ everyday, and considering our role as a part of the whole.

***

This article was edited by Abigail D’Angelo